Friday, November 21, 2014

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

Thursday, October 30, 2014

Wednesday, September 10, 2014

Saturday, September 6, 2014

How William Gibson Coined “Cyberspace”

The moment when fragments of reality were “mushed together” to describe a new realm.

William Gibson, thirty-four at the time, used a strange new word in his short story “Burning Chrome” to describe — presage, really — the emerging ecosystem sprouted by computer networks. But it wasn’t until Gibson used it again in his 1984 novel Neuromancer (public library) that the new term — “cyberspace” — caught on like cultural wildfire.

In this excerpt from his conversation with The New York Public Library’s Paul Holdengräber — the conversation in which Gibson provided his witty 7-word autobiography — the author explains how and why he coined “cyberspace”

See Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ae3z7Oe3XF4

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Share on Tumblr

William Gibson, thirty-four at the time, used a strange new word in his short story “Burning Chrome” to describe — presage, really — the emerging ecosystem sprouted by computer networks. But it wasn’t until Gibson used it again in his 1984 novel Neuromancer (public library) that the new term — “cyberspace” — caught on like cultural wildfire.

In this excerpt from his conversation with The New York Public Library’s Paul Holdengräber — the conversation in which Gibson provided his witty 7-word autobiography — the author explains how and why he coined “cyberspace”

See Video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ae3z7Oe3XF4

I wanted that sense of other realm, a sense of agency within my daily life, looking for bits and pieces of reality that could be cobbled into the arena I needed.A quarter century later, Gibson coined another exquisitely apt term for a cultural phenomenon — “personal micro-culture,” that absolutely essential tool in our architecture of character as creative people and human beings.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Share on Tumblr

Bringing you ad-free Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours each month. If it brings you any joy, please consider supporting with a small donation.

Thursday, August 28, 2014

I am here

I am here. Those three words contain all that can be said – you begin with those words and you return to them. Here means on this earth, on this continent and no other, in this city and no other, and in this epoch I call mine, this century, this year. I was given no other place, no other time, and I touch my desk to defend myself against the feeling that my own body is transient. This is all very fundamental, but after all, the science of life depends on the gradual discovery of fundamental truths.

I have written on various subjects, and not, for the most part, as I would have wished. Nor will I realize my long-standing intention this time. But I am always aware that what I want is impossible to achieve. I would need the ability to communicate my full amazement at “being here” in one unattainable sentence which would simultaneously transmit the smell and texture of my skin, everything stored in my memory, and all I now assent to, dissent from. However, in pursuing the impossible, I did learn something. Each of us is so ashamed of his own helplessness and ignorance that he considers it appropriate to communicate only what he thinks others will understand. There are, however, times when somehow we slowly divest ourselves of that shame and begin to speak openly about all the things we do not understand. If I am not wise, then why must I pretend to be? If I am lost, why must I pretend to have ready counsel for my contemporaries? But perhaps the value of communication depends on the acknowledgment of one’s own limits, which, mysteriously, are also limits common to many others; and aren’t these the same limits of a hundred thousand years ago? And when the air is filled with the clamor of analysis and conclusion, would it be entirely useless to admit you do not understand?

I have read many books, but to place all those volumes on top of one another and stand on them would not add a cubit to my stature. Their learned terms are of little use when I attempt to seize naked experience, which eludes all accepted ideas. To borrow their language can be helpful in many ways, but it also leads imperceptibly into a self-contained labyrinth, leaving us in alien corridors which allow no exit. And so I must offer resistance, check every moment to be sure I am not departing from what I have actually experienced on my own, what I myself have touched. I cannot invent a new language and I use the one I was first taught, but I can distinguish, I hope, between what is mine and what is merely fashionable. I cannot expel from memory the books I have read, their contending theories and philosophies, but I am free to be suspicious and to ask naïve questions instead of joining the chorus which affirms and denies.

Intimidation. I am brave and undaunted in the certainty of having something important to say to the world, something no one else will be called to say. Then the feeling of individuality and a unique role begins to weaken and the thought of all the people who ever were, are, and ever will be – aspiring, doubting, believing – people superior to me in strength of feeling and depth of mind, robs me of confidence in what I call my “I.” The words of a prayer two millennia old, the celestial music created by a composer in a wig and jabot make me ask why I, too, am here, why me? Shouldn’t one evaluate his chances beforehand – either equal the best or say nothing. Right at this moment, as I put these marks to paper, countless others are doing the same, and our books in their brightly colored jackets will be added to that mass of things in which names and titles sink and vanish. No doubt, also at this very moment, someone is standing in a bookstore and, faced with the sight of those splendid and vain ambitions, is making his decision – silence is better. That single phrase which, were it truly weighed, would suffice as life’s work. However, here, now, I have the courage to speak, a sort of secondary courage, not blind. Perhaps it is my stubbornness in pursuit of that single sentence. Or perhaps it is my old fearlessness, temperament, fate, a search for a new dodge. In any case, my consolation lies not so much in the role I have been called on to play as in the great mosaic-like whole which is composed of the fragments of various people’s efforts, whether successful or not.

I am here – and everyone is in some “here” – and the only thing we can do is try to communicate with one another.

”| — | Czeslaw Milosz, from My Intention |

Saturday, August 16, 2014

Sunday, August 10, 2014

Not Sure If I Should Be Pleased or Worried By This

Wednesday, August 6, 2014

Preferred narratives

“This, too, is how disciplinary power works, by colonizing us from within, so we become the willing inhabitants of the worlds specified by our preferred narratives”

| — | Foucault, 1980 |

Monday, August 4, 2014

Saturday, August 2, 2014

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Tuesday, July 29, 2014

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Walk About

There are some great lines, very lovely lines in this book. There are some great insights into the human condition: "people like to think that other people are totally unlike them-- but these differences are, in reality, for most functions, rather small." (p. 205) I loved the walks through NYC and Brussels. The layers of history which existed in both places just beneath the surface of the "modern" world. But, but, but it just kind of rambles along to a very rambling end. Most of the time I liked it, but the sexual assualt accusation came out of nowhere (maybe I wasn't paying attention to the ramble that started the novel drifting toward that revelation) and the end ramble about the dying birds and the Statue of Liberty, must be some kind of significance which escapes me.

(July 27, 2014)

(July 27, 2014)

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Friday, July 18, 2014

Monday, July 14, 2014

Sunday, June 15, 2014

Monday, June 9, 2014

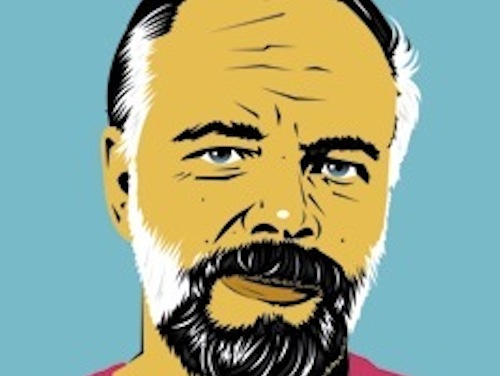

Philip K. Dick's Favorite Classical Music

What did Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and A Scanner Darkly author Philip K. Dick, that visionary of our not-too-distant dystopian future, listen to while he crafted his descriptions of grim, psychologically (and sometimes psychedelically) harrowing times ahead? Mozart. Beethoven. Mahler. Wagner. Yes, while looking textually forward, he listened backward, soundtracking the constant workings of his imagination with classical music, as he had done since his teenage years. As Lejla Kucukalic writes in Philip K. Dick: Canonical Writer of the Digital Age:

After graduating from high school in 1947, Dick moved out of his mother’s house and continued working as a clerk at a Berkeley music store, Art Music. “Now,” wrote Dick, “my longtime love of music rose to the surface, and I began to study and grasp huge areas of the map of music; by fourteen I could recognize virtually any symphony or opera” (“Self-Portrait” 13). Classical music, from Beethoven to Wagner, not only stayed Dick’s lifelong passion, but also found its way into many of his works: Wagner’s Goterdammerung in A Maze of Death, Parsifal in Valis, and Mozart’s Magic Flute in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

At his Forteana Blog, author Andrew May credits Dick with, given his pop-cultural status, “a decidedly uncool knowledge of classical music.” He cites not just Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen in the introduction to A Maze of Death, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis in Ubik, or the part of The Game-Players of Titan where “a teenaged kid forks out 125 dollars for a vintage recording of a Puccini aria,” but an entire early story which functions as “(in my opinion) a pure exercise in classical music criticism.” In 1953′s “The Preserving Machine,” as May retells it, an eccentric scientist, “worried that Western civilization is on the point of collapse, invents a machine to preserve musical works for future generations” by encoding it “in the form of living creatures. Unfortunately, as soon as the creatures are released into the environment, they start to adapt to it by evolving into different forms, and the music becomes distorted beyond recognition.”

Though no doubt an astute speculator, Dick seems not to have foreseen the fact that our era suffers not from too few means of music storage but, perhaps, too many. None of his visions presented him with, for example, the technology of the Spotify playlist, an example of which you’ll find at the bottom of this post. In it, we’ve assembled for your enjoyment some of Dick’s favorite pieces of classical music. The songs come scouted out by Galleycat’s Jason Boog, who links to them individually in his own post on Dick, classical music, and May’s writing on the intersection of those two cultural forces. Listen through it while reading some of Dick’s own work — don’t miss our collection of Free PKD — and you’ll understand that he cared about not just the anxieties of humanity’s future or the great works of its past, but what remains essential throughout the entire human experience. These composers will still appear on our playlists (or whatever technology we’ll use) a hundred years from now, and if we still read any sci-fi author a hundred years from now, we’ll surely read this one.

The 11 hour playlist (stream below or on the web here) includes Bach’s Goldberg Variations, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and Fidelio, Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Wagner’s Parsifal, and Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 (Resurrection). If you need to download Spotify, grab the software here.

Related Content:

33 Sci-Fi Stories by Philip K. Dick as Free Audio Books & Free eBooks

Robert Crumb Illustrates Philip K. Dick’s Infamous, Hallucinatory Meeting with God (1974)

The Penultimate Truth About Philip K. Dick: Documentary Explores the Mysterious Universe of PKD

Philip K. Dick Theorizes The Matrix in 1977, Declares That We Live in “A Computer-Programmed Reality”

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Listen to Philip K. Dick’s Favorite Classical Music: A Free, 11-Hour Playlist is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

The post Listen to Philip K. Dick’s Favorite Classical Music: A Free, 11-Hour Playlist appeared first on Open Culture.

Saturday, June 7, 2014

Why I Started RFB

“Nowadays I know the true reason I read is to feel less alone, to make a connection with a consciousness other than my own.”

| — | Zadie Smith, Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays |

Friday, June 6, 2014

Saturday, April 26, 2014

Friday, April 25, 2014

Monday, January 27, 2014

Peter at the Gate!?!?!?!

So, is it really that obvious: PETER at the Gate to paradise, listening to people's stories in order to let them in or not? We are judged by our story. It doesn't matter if it is really our story, just that it is a good story.

"Question: It's nothing terrible. Everyone tells his story the best he can.

Answer: I didn't make anything up. That's how it all was. Do you believe me?

Question: It makes no difference whether I do or don't." p. 47

I love this. We all tell our story the best we can, and in by the end we just hope it comes out well. The story we are telling is our life. We incorporate others stories because those stories have become a part of our lives, thus they have become our story as well. "In short, everything everywhere is this story." p. 49 And eventually the story the answer is telling is being told as well by the question in a collaborative storytelling.

Even within the first 100 pages the strands of narrative are unravelling as they are being woven and then rewoven again.

the "truth" comes out in the liminal zone of culture: (just to bring us back to bhabha).

Lovely Lovely fun.

"Question: It's nothing terrible. Everyone tells his story the best he can.

Answer: I didn't make anything up. That's how it all was. Do you believe me?

Question: It makes no difference whether I do or don't." p. 47

I love this. We all tell our story the best we can, and in by the end we just hope it comes out well. The story we are telling is our life. We incorporate others stories because those stories have become a part of our lives, thus they have become our story as well. "In short, everything everywhere is this story." p. 49 And eventually the story the answer is telling is being told as well by the question in a collaborative storytelling.

Even within the first 100 pages the strands of narrative are unravelling as they are being woven and then rewoven again.

the "truth" comes out in the liminal zone of culture: (just to bring us back to bhabha).

Lovely Lovely fun.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)